Weekly - China launches its first asteroid sample return mission and more

🟢 Weekly Space News - Quick and Easy.

Our Engagement Palette!

Check out our colour-coded system for our weekly space news:

🟤 Brown: For weeks that are mundane and bland.

🟡 Yellow: For fairly interesting weeks.

🟢 Green: For the most exciting weeks.

This Palette will help you decide if this week’s news is worth your time!

This week ranks green 🟢 on the Engagement Palette.

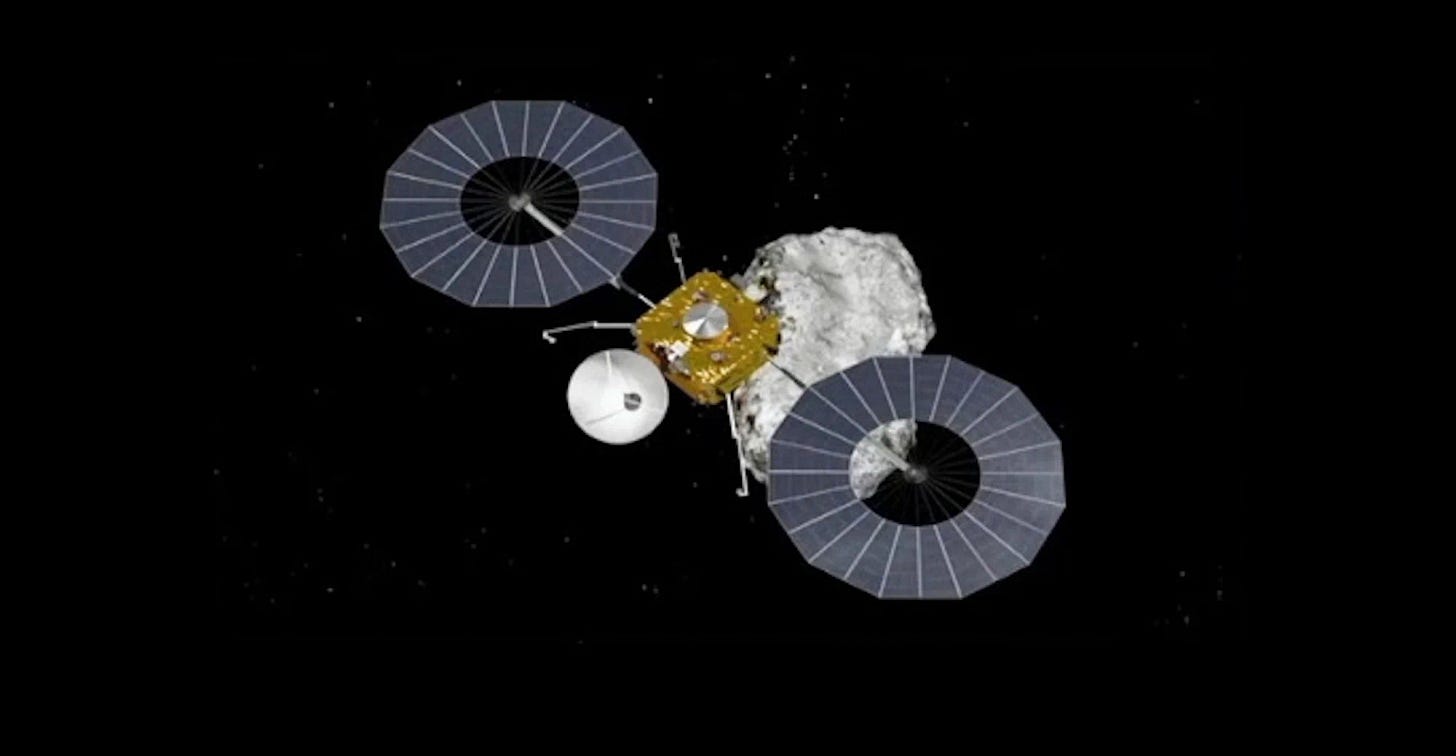

China launches its first asteroid sample return mission

Last week, China launched its first asteroid sample return mission - Tianwen-2. The mission is headed to the asteroid ‘469219 Kamoʻoalewa’, which actually orbits the Sun, but appears to orbit the Earth, because it is very close to it. The mission is expected to reach the asteroid by July 2026 and return to Earth by November 2027 after collecting 100g of samples.

SpaceX flight-9 fails

Last week, SpaceX’s 9th test flight of its Starship rocket failed again for the 3rd time in a row. The rocket blasted off fine, but when the main stage separated from the booster, it started spinning uncontrollably. The booster fell into the Gulf of Mexico instead of making a controlled splashdown. The spaceship was unable to deploy its dummy satellites because a door got stuck. It broke up in orbit. The ninth flight, however, did surpass the previous 2 flights, and this time was even reusing a previous booster.

Scientists find largest black-hole jet ever

Last week, scientists using the groundbreaking LOFAR radio telescope discovered the largest black-hole jet ever. When a black hole starts consuming the matter around it, the particles spin at very high speeds around the black hole, creating a bright accretion disk. Sometimes, some of these particles escape the disk and are channelled away from the black hole, forming a jet with 2 lobes at either end, forming a quasar system. This quasar, J1601+3102, was formed when the universe was just 1.2 billion years old. Now its jet's length is nearly 2 times the diameter of the Milky Way galaxy.

Hubble constant solved?

The Hubble constant has been a value under debate for a long time by scientists that determines how fast the universe is growing. One method to measure this is the cosmic microwave background, which is radiation left over from the Big Bang. Another method is to measure how far stars and galaxies are from the Earth. Up until now, these 2 methods have given different values. Recently, more precise data from the James Webb telescope has given a more accurate value for the second method, which now matches the first method’s value. The Hubble constant has been solved for now.